Types of carbohydrates to avoid:

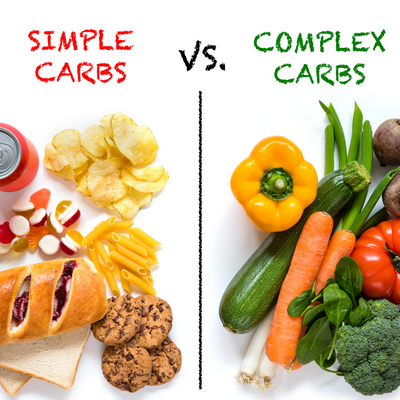

There are two kinds of carbohydrates, simple and complex. As these carbohydrates break down, blood glucose rises, and insulin is released. Insulin stimulates the cells to uptake glucose for storage in muscle and fat. The rate at which glucose is absorbed is vital in controlling blood glucose levels and insulin release. The effect that a carbohydrate has on the blood glucose levels is called a glycemic response. Another way to classify carbohydrates is as high and low glycemic index (GI) carbohydrates. High GI carbs are rapidly absorbed, causing a fast insulin spike. While low GI foods are slowly absorbed over time, reducing the chance of a large insulin spike. Lower GI foods result in a lower blood glucose level and a more gradual blood glucose fall. The glycemic load (GL) is the GI of a food multiplied by the grams of carbohydrates, and it is also an important consideration. In order to maintain a steady glucose level and prevent insulin resistance, a diet low in GI and GL is prudent (Gropper, Smith, & Carr, 2018).

What percent of the diet should come from carbohydrate, fat, and protein and why?

Current RDA are as follows for a female age 55:

Carbohydrates 45-65%

Fat 20-35%

Protein 10-35%

(US Department of Health and Human Services & US Department of Agriculture, 2015)

Carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, as they are metabolized, eventually produce ATP and energy via the Kreb Cycle. Balancing these macronutreints is essential. Carbohydrates provide the largest amount of glucose and fastest source of energy. A rise in blood sugar is delayed, digestion is slowed, and blood sugar remains stable when fat is consumed along with a carbohydrate. The body utilizes protein for growth, maintenance, and energy. Proteins are broken down into amino acids (Cotton, n.d.).

Multiple macronutrient distributions would be advantageous for patients. However, I would prescribe a cardiometabolic diet with a macronutrient distribution as follows:

Carbohydrates 40%

Fat 30%

Protein 30%

This distribution supports lower glucose and postprandial insulin. Foods in the cardiometabolic plan are low GI.

Can a patient simply add a fiber pill to this breakfast and feel secure that their fiber needs for the day are met?

Fibers supplementation at 20 grams a day is beneficial in glycemic control, but supplementation should never replace whole foods. Simply adding fiber to a high GI food does not negate that food's negative effects (Gropper, Smith, & Carr, 2018).

Understanding the role fiber has in digestion and absorption:

There are soluble and insoluble fibers. Soluble fibers dissolve in water and form a gel-like substance. Insoluble fibers do not dissolve, add to the bulk of the stool, and improved stool transit. Fiber intake can increase the absorption of some minerals like calcium, promote the growth of good bacteria in the gut, and increase the sensation of fullness through the production of glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY). Soluble fibers are viscous, which causes slow gastric emptying, and macronutrient absorption, leading to lower postprandial blood glucose and insulin level (Lattimer & Haub, 2010).

How the types of carbohydrates contribute to obesity:

High GL meals limit the supply of metabolic fuels throughout the late postprandial period, decrease fat oxidation, reduce energy expenditure, stimulate stress hormone production, and increase voluntary intake of food. Increased fat storage can occur over the long term, with repeated postprandial cycles after meals rich in GL. High-carbohydrate diet triggers postprandial hyperinsulinemia, induces calorie deposition in fat cells rather than oxidation in lean tissues, leading to weight gain by increasing appetite and reducing metabolic rate (Ludwig & Ebbeling, 2018).

What are the possible fates of glucose in the body?

The majority of glucose ends up in various tissues' cells, but some are transported to the liver. In the cell, glucose is converted to pyruvate and used in the Kreb's Cycle for energy production. When there is excess energy, the glucose is converted to glycogen and stored in the liver. When the liver storage of glycogen is full, glucose is stored as fat (Gropper, Smith, & Carr, 2018).

References

Cotton, M. (n.d.). Balancing Carbs, Protein, and Fat. Kaiser Permanente. Retrieved September 5, 2020, from https://wa.kaiserpermanente.org/healthAndWellness?item=%2Fcommon%2FhealthAndWellness%2Fconditions%2Fdiabetes%2FfoodBalancing.html

Gropper, S. S., Smith, J. L., & Carr, T. P. (2018). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01621.x

Lattimer, J. M., & Haub, M. D. (2010). Effects of dietary fiber and its components on metabolic health. Nutrients, 2(12), 1266–1289. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu2121266

Ludwig, D. S., & Ebbeling, C. B. (2018). The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity: Beyond “calories in, calories out.” JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(8), 1098–1103. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2933

US Department of Health and Human Services & US Department of Agriculture. (2015). Dietary Guidelines for Americans: 2015-2020. Eight Edition. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118889770.ch2

*These statements are not meant to diagnose or treat. You should consult your health care provider before starting any new diet, exercise, or supplement.